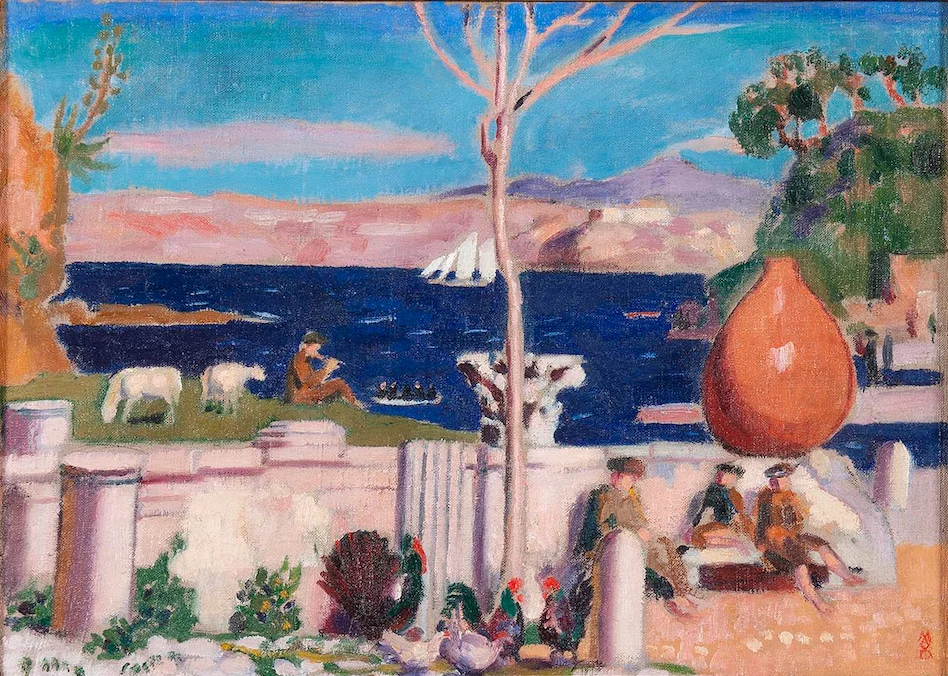

This is the first in a series where I want to delve deeper into the topics of relationship. The first part is an exploration into Jung’s archetypes and how love is a mutual becoming.

I’ve been mulling over this all morning, wondering what I want to write about love - the state that morphs into every crevice of one’s consciousness - romantic, platonic, familial.

What do I really know about it? Less than I’d like, more than I admit.

I went to grab a coffee earlier today. The barista knows my order by now - Latte, oat milk, hot. Today she slides over not just my drink but a small envelope, worn at the edges like it’s been carried around for a while. Her eyes meet mine for just a moment longer than usual:

“Someone left this for you,” she says, then turns to the next customer.

Inside, three words in unfamiliar handwriting:

Love is coming.

I stand there, coffee cooling, envelope light in my hands. Part of me wants to ask who left it, when, why. The other part understands that some gifts are meant to stay mysteries. Like finding a dollar bill in an old coat pocket, or hearing your favorite song on a stranger’s radio - some moments of grace are better left unexplained. I pocket the note. Outside, February wind cuts through my jacket. But I’m thinking about how strange it is, how a few words from an unknown hand can make a person feel less, alone in the times of a loneliness epidemic.

From childhood through adulthood, we are drawn into relationships not simply to be loved, but to feel that we are part of something greater than ourselves. Think of joining a football team, working in fourth spaces, playing hanging with friends, etc. This longing for connection is somewhat primal, encoded deep inside our DNAs. Yet, this connection is often mistaken for the desire for another person’s affection, when it is in truth a yearning for a sense of home—a state of being where one is seen, accepted, and integrated.

The notion that love is about belonging challenges the popular narrative that it is a transaction or a fleeting emotional high. Instead, it proposes that love is an enduring, almost sacred, commitment to self-recognition and mutual acceptance. This understanding reframes our loneliness: isolation is not a lack of love, but rather a disconnection from the fundamental truth that we belong.

a projection of the Anima/Animus

Jungian psychology posits that romantic attraction begins with the projection of the anima (the unconscious feminine aspect in men) or animus (the unconscious masculine aspect in women) onto another person. This projection creates the illusion of “completeness,” as the beloved becomes a vessel for unintegrated parts of the self. For example, a man might idealise a partner as the embodiment of nurturing sensitivity—qualities he has repressed in his conscious identity—while a woman might project assertiveness or intellectual rigor onto a partner, mirroring her latent animus. Jung described this dynamic as a “religious search” for wholeness, where the lover unconsciously seeks to reunite with the lost halves of their psyche through another.

Where love rules, there is no will to power; and where power predominates, there love is lacking. The one is the shadow of the other.

However, such projections are inherently unstable. When relationships falter under the weight of unmet archetypal expectations, the disillusioned ego often retreats into shame or resentment, mistaking the collapse of projection for the failure of love itself.

defensive isolation, and its shadows

Heartbreak ruptures the psyche’s fragile equilibrium, triggering a numinous experience—an encounter with the shadow, the repository of rejected traits and unresolved traumas. To avoid confronting this darkness, individuals often erect psychological barriers. These walls manifest as emotional detachment, intellectualisation of intimacy, or compulsive self-reliance—all attempts to “protect” the ego from further annihilation. For instance, an individual going through post-divorce isolation 1 or and individual dealing with limerence illustrate how the shadow’s fear of vulnerability fuels self-sabotage. Jung observed that such defenses arise from a primal terror of psychic disintegration:

The body will not allow itself to be exposed to annihilation. It’s prepared to annihilate itself to avoid that

Yet these walls, while temporarily numbing pain, perpetuate a cycle of alienation. By refusing to engage with the shadow’s raw material—grief, rage, longing—the individual stagnates, mistaking the atrophy of emotional risk for “strength”.

Jungian belonging transcends social affiliation; it is rooted in the collective unconscious—the shared reservoir of archetypes and primordial symbols that bind humanity. When emotional walls block access to this deeper stratum, individuals experience belonging as an intellectual concept rather than an embodied reality. As such, a recurring dream of “packing a suitcase” with unresolved urgency epitomises this disconnect: the psyche yearns for symbolic “homecoming” but remains trapped in superficial preparations.

True belonging, Jung argued, requires surrendering the ego’s insistence on control. In The Red Book, he wrote that the soul “circulates energy both outwardly and inwardly” only when the individual dares to love without guarantees. This aligns with accounts of heartbreak survivors who, after dismantling defenses, discover belonging through radical self-acceptance rather than external validation.

Jung viewed heartbreak as an initiatory ordeal, compelling the ego to confront its limitations and renegotiate its relationship with the Self. The key lies in holding the tension between love’s idealised projections and its messy realities. For example, a woman who idealises her partner as a “hero” animus figure might, through betrayal or loss, confront her own repressed assertiveness—a step toward reclaiming projection as inner resource.

Alain de Botton’s assertion that love is a fundamental human requirement stems from his analysis of existential loneliness—“the tax we pay for consciousness”. Yet the anguish of feeling “out of love” arises not from love’s absence but from a misalignment between our idealised projections of connection and the raw, unvarnished reality of relationship. De Botton frames loneliness as an inevitable byproduct of self-awareness, a tax levied by our capacity to reflect on existence. Romanticism, he argues, sold humanity a dangerous myth: that a soulmate could resolve this existential solitude. When reality fails to meet this ideal—as it invariably does—many retreat into emotional isolation, interpreting disillusionment as proof of love’s impossibility rather than its maturation.

What must endure isn't "love" but friendship and trust.

Jungian-Bottonian implies that love as an antidote to modernity’s existential despair. Alain de Botton secularises the dynamic flow of love, as the “democracy of doubt”. Here, love becomes a rebellion against nihilism, not through grand gestures but through daily acts of attention: the way a hand adjusts to another’s in the dark, or the pause before voicing a difficult truth.

Alain Badiou’s warning against algorithmic dating resonates here: by sanitising love of risk, we sterilise its transformative potential. The surge in “religious but not spiritual” affiliations reflects a hunger for transcendent meaning—a void that Jungian belonging fills through engagement with archetypal narratives, while de Botton advocates for secular rituals (like shared meals or curated art) to cultivate communal grace. Both solutions reject individualism’s isolation, proposing instead that love is “the quiet revolution of mutual becoming”

interpretation.

I know it is so cliche, but before we can truly love another, we must first learn to love ourselves. When we view love through the lens of belonging, we recognise that it is as much an internal state as it is an external interaction. The greatest acts of love often begin with the willingness to confront our internal conflicts—the projections, the shadows, the silent yearnings for radical self-acceptance. Only when we learn to sit with our discomforts and embrace our true selves can we truly share ourselves with another.

Belonging begins with recognising that we are enough as we are, even in our messiness and imperfections. When we nurture our inner selves through honest self-reflection and care, we lay the groundwork for relationships that are not about filling a void, but about sharing a journey.

I have a hard time internalising the idea of loving myself, simply because:

- Humans are innately egotistical, and only you can look after the self. If you just sit there and thinks someone would help you heal or teach you to change your oil, then idea of life is somewhat naive from your point of view. Self-love should emerge naturally from this arrangement. Yet I find myself perpetually turned outward, my hands extended in offering. My instinct is to give, to pour, to fill other vessels while my own runs dry—a peculiar form of selfishness disguised as generosity. In the spaces between caring for others, I’ve somehow misplaced the grammar of self-regard, forgotten how to form those small, essential sentences: I need some rest.

- To find love is to find a friend, but I’m too protective of my friendship to allow myself falling in love.

- My manager once said, “Too much opportunity creates analysis paralysis.” Same with love. When you approach relationships like a kid at Build-A-Bear Workshop (I’ll take the loyalty of a Golden Retriever, the wit of a Twitter troll, and… ooh, let’s stuff in some trauma resilience!), you end up with a Frankenstein’s monster of unmet expectations

- This is not permanent, but currently dealing with grief of losing a friend 2

But sometimes, You just have to stop optimising and give up on being lonely

Let me be seen.

Let me be annoyed.

Let me belong to myself first,

so I can stop treating love

like an exorcism.

I keep thinking about what C said: “You have to learn to be selfish.”

But maybe that’s backward. Maybe true selfishness isn’t building higher walls but learning to live without them. To be present even when presence hurts.

The hardest part isn’t being alone. It’s explaining to well-meaning friends why you choose it. How do you tell someone that sometimes loneliness feels like the closest thing to belonging? That there’s a difference between being lonely and being lost?

But then there are moments like finding that envelope. Small reminders that even in isolation, we’re tethered to each other in ways we can’t always see. That love isn’t just romantic partnership or family bonds - it’s also the anonymous kindness of leaving messages for strangers to find.

I don’t know if love is coming. But I know this: every day I choose to get up, to walk to this coffee shop, to sit among other humans pursuing their own solitudes. And maybe that’s its own kind of love. Maybe belonging isn’t something we find but something we practice, like patience or hope.

The envelope sits on my desk now, a small spot of red against white papers. I could spend hours theorising about who left it, analysing the meaning behind the message. Instead, I let it be what it is: a reminder that even in a world that often feels too big and too empty, someone took the time to write three words and leave them where they might be found.

Happy Valentines everyone, do something that you love today, if you are soloing it (I will definitely go out and enjoy some good food and books).

Here’s are some media, quotes, and unstructured thoughts. I hope you might find something out of it:

figure2: Zuck - Ian McEwan once said:

The way a hand adjusts to another’s in the dark, the pause before a difficult truth

Once can said that essence of love lies within the granular act of attention. Love, is the antidote to solipsism: To project is human, to retract that projection and see others is divine. - Belonging is a verb. It thrives not in static harmony but in the messy, glorious work of mutual revision.

- Thérèse and Isabelle, by Violette Leduc

- an authentic read on queer loves, by a French author. This is the first book that I read in French, let’s just say that Claude is my translator’s partner.

- I watched La Belle Personne (2003) starring Léa Seydoux and Louis Garrel

- Draws parallels to “La Princesse de Clèves,” using the classic novel’s themes of duty, honor, and forbidden love to explore modern teenage experiences.

- Junie’s struggle to find her place in the world and understand her own desires reflects a broader search for identity and belonging. The film suggests that this journey is fraught with uncertainty and that true belonging comes from within, rather than from external validation.

-

i have a recurring dream that we’re visiting you. every time, i come with different people. and every time, i don’t know how we got up there. we’re just there. it’s empty at first, and then you appear. i bring your favourite cookies, we walk around and talk about what has changed. but i always wake up, i’m hundreds of kilometres away, and even if we went to where we remember you, i don’t even know if you’d be there. — typo.love, by Kelly

- Work-related: structured decoding for vLLM v1 should be out promptly, in addition to a project I have been working on for the past 5 months that is in the realm of UX and productionising interpretability